Introduction

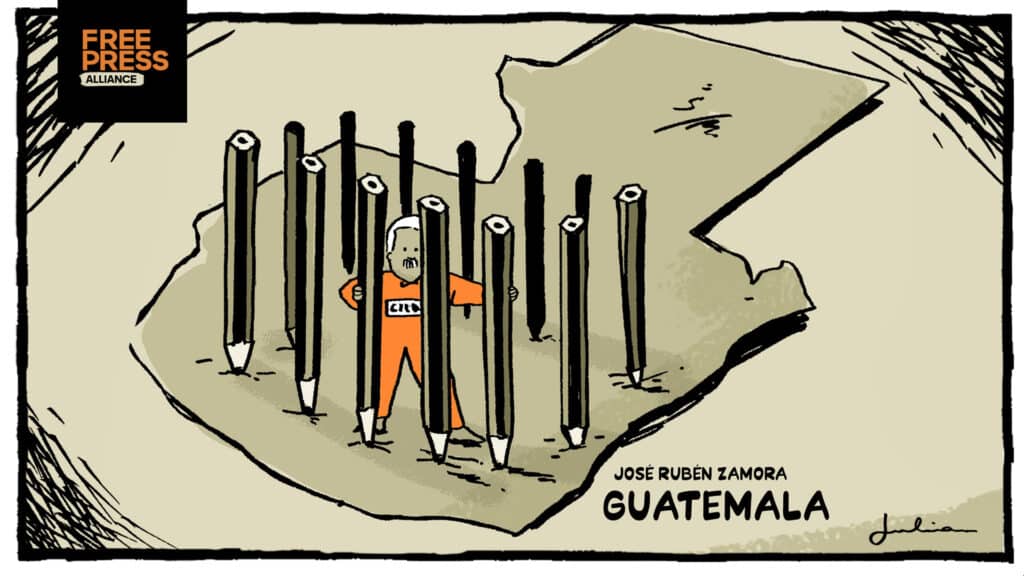

This August marks three years since the arrest of Guatemalan journalist José Rubén Zamora, founder of the now defunct elPeriódico, one of Central America’s most important investigative outlets. His imprisonment, under charges widely criticized as politically motivated, is emblematic of a broader pattern: a deliberate campaign to silence independent journalism in Guatemala. From mainstream media to rural radio, the government’s failure to protect, and in some cases its active persecution of, the press has become one of the greatest threats to Guatemala’s fragile democracy.

The targeting of independent media

Zamora’s arrest in July 2022, and the subsequent closure of elPeriódico in 2023, sent a chilling message across the Guatemalan press. Despite international outcry, including statements from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and Human Rights Watch, the judicial process against Zamora has been marred by irregularities, lack of due process, and limited access to defense. As CPJ stated, “the charges against Zamora appear designed to silence a critical voice.”

This case is not isolated. Under the administration of Alejandro Giammattei and, more recently, Bernardo Arévalo, journalists across the country have reported increased surveillance, threats, and spurious legal action. While Arévalo promised to prioritize press freedom, organizations such as Reporters Without Borders (RSF) have noted that “the judicial system remains deeply compromised, and journalists continue to face legal harassment.”

Community journalism: The first line of defense

Beyond Guatemala City, a quieter, but no less dangerous, battle is being fought. Community journalism, particularly in Indigenous territories, has long served as a bulwark against state neglect and corporate abuse. Rooted in local culture, often multilingual, and operated with minimal resources, community media gives voice to populations historically silenced by the state.

As noted in the 2025 “Informe del Grupo de Observación de la Libertad de Prensa en Centroamérica”, these outlets are not simply alternative media, they are “agencies of collective memory and resistance,” especially in areas most affected by violence, displacement, and extractivism.

A double standard: Criminalization and marginalization

Despite their vital role, community journalists operate under constant threat. Guatemala still fails to legally recognize community radio stations, leaving many in a state of permanent illegality. Efforts like the proposed Law 4087, which would grant legal status to these outlets, have been systematically blocked by commercial broadcasters.

The result is violent repression. In 2006, Radio Ixchel was raided by over 40 police officers; in 2022, Radio Nakoj staff faced intimidation and confiscation of equipment after reporting on local corruption. Journalists like Carlos Choc, Norma Sancir, and Anastasia Mejía have been criminalized for their reporting. Mejía, for instance, spent 37 days in jail without trial for documenting a local protest in Joyabaj, Quiché.

Systemic violence and repression

According to testimonies gathered by ARTICLE 19, CPJ, and others, community journalists are targeted by local elites, municipal authorities, extractive industries, and organized crime. In 2024, journalist Narciso Marcos Chegüén survived an armed attack after reporting on corruption in Chiquimula (Article 19 / FLIP mission report). That same year, Ismael Carmen Alonzo González, a community journalist, was murdered (ibid).

The gendered and racialized dimensions of these attacks are especially alarming. Women Indigenous journalists face discrimination not only for their reporting but for defying stereotypes. Journalist Irma Chis was denied access to a courtroom while covering a hearing, because her traditional dress made it “unbelievable” she was a reporter. This triple discrimination, by gender, ethnicity, and profession, intensifies their vulnerability.

Resistance and resilience

Yet, community journalism survives. More than that, it changes shape. From denouncing illegal logging to promoting bilingual education, these journalists act as agents of transformation. One community journalist recalled reporting on deforestation after locals called for help. The story went viral, caught national attention, and halted the destruction (Prensa Comunitaria).

Organizations like Prensa Comunitaria, Radio Ixchel, and the Federación Guatemalteca de Escuelas Radiofónicas (FGER) continue to produce news in Indigenous languages and build trust with their communities, often without pay, legal protection, or state support.

A press worth defending

In 2021, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled in the landmark case Pueblos Indígenas Maya Kaqchikel de Sumpango vs. Guatemala that the country must recognize and protect Indigenous community media. Four years later, implementation remains largely symbolic.

Guatemala cannot rebuild its democratic institutions without addressing the deep-rooted inequalities of how it treats its media. Freedom of expression must extend beyond urban newsrooms to the rural mountains of Totonicapán, the lakes of Atitlán, and the jungles of Petén. Legal recognition, protective policies, and structural reform are long overdue.

Conclusion

Press freedom in Guatemala is not only under siege, but is also being actively dismantled. From the persecution of nationally renowned journalists to the criminalization of grassroots communicators, the state has cultivated an environment where telling the truth can cost you your freedom, or your life.

But journalism in Guatemala persists. And nowhere is it more courageous, more urgent, and more essential than in the hands of those who speak not for the powerful, but for the people.