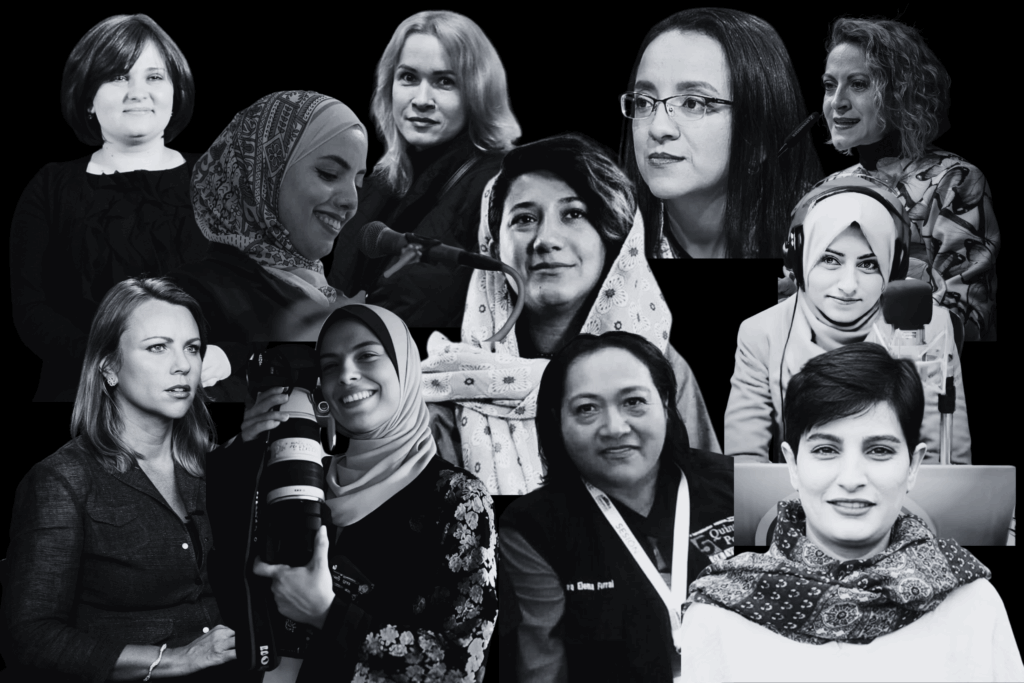

Being a woman in certain professions entails danger due to the lack of protection. In many regions of the world, being a woman and a journalist is a double sentence to persecution. This article reflects on the specific challenges faced by female reporters in contexts of war, authoritarian regimes, and patriarchal societies, as well as the strategies they adopt to resist and continue reporting.

Journalism has become a high-risk profession in many parts of the world. But when the one holding the microphone, notebook, or camera is a woman, the dangers multiply. Women journalists not only face the inherent threats of violent or authoritarian contexts, but also a specific type of gender-based violence: sexual harassment, smear campaigns, surveillance of their bodies and a systematic silencing that has little to do with professional criticism and everything to do with structural machismo.

From Mexico to Afghanistan, and across Iran and Palestine, more and more female reporters are being forced to choose between their calling and their physical safety. Some risk everything. Others choose exile or anonymity to keep reporting. All of them face a common challenge: practicing journalism in a world that still harshly punishes women who refuse to be silent.

-

Gender-based violence as a weapon against the press

In many cases, harassment against women journalists is not limited to physical spaces. Social media has become a real battlefield, where sexist insults, rape threats, and misogynistic comments seek to break their credibility and mental health. In countries like India, Brazil, or Turkey, studies show that women journalists are attacked online three times more often than their male colleagues, as documented by a global report from UNESCO and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ). Not for what they write, but for who they are.

Violence is also present in newsrooms. Many women journalists face wage inequality and a macho culture that relegates them to “soft” topics or excludes them from complex coverage for being considered “vulnerable,” according to a study by the International Federation of Journalists. In conflict zones, that perception becomes a double-edged sword: they are denied access, but also exposed to sexual assault, blackmail, and threats when they do manage to enter.

A case that shook international journalism was that of South African reporter Lara Logan, a CBS News correspondent, who was brutally sexually assaulted by a mob in Cairo’s Tahrir Square in 2011 while covering the Arab Spring protests. Logan was separated from her crew, beaten, and sexually assaulted for more than 20 minutes by dozens of men in what she later described as an attack clearly intended to “break her body and silence her voice.” Her testimony, shared after a long recovery, broke a major taboo surrounding sexual violence against war correspondents.

The case of María Elena Ferral, murdered in Veracruz in 2020 after receiving threats for her reporting on political corruption, highlights the deadly risk faced by those who break the silence in areas dominated by organized crime. And yet, the violence does not always end in death: many others, like Russian journalist Maria Ponomarenko, have been imprisoned, tortured, or forced into exile.

The message is clear: it’s not only the act of reporting that’s punished, but the fact that a woman is doing it. A woman who investigates, criticize, and refuses to submit.

-

Women reporting from the frontlines

Journalism in conflict zones is an act of bravery that, for women, comes with double the risk: that of war and that of gender-based violence.

- In Gaza, photojournalist Fatima Hassouna was killed on April 16, 2025, in an Israeli airstrike that destroyed her home. Hassouna, 25, was known for her documentary work and had just been selected for the Cannes Festival.

- In November 2023, freelance journalist Ayat Khadoura died with her family in an airstrike in Beit Lahia. She was known for her podcasts about daily life in Gaza. Her last video, recorded just days before her death, was a direct message to the world and went viral after the attack.

- On October 26, 2023, Duaa Sharaf, host at Al-Aqsa Radio, was killed alongside her daughter in a bombing in Al-Zawaida. Her death sparked a wave of tributes that turned her into a symbol of the risks faced by Palestinian women journalists.

Over 200 journalists have lost their lives in Gaza since the war began in October 2023, and at least 24 of them, women, were killed in attacks on their homes.

These cases illustrate the extreme danger faced by female reporters in war zones. Their presence, even in the crossfire, allows the world to be documented, but it also makes them a target.

-

Institutional harassment and censorship in authoritarian regimes

In many authoritarian contexts, the silencing of women journalists is not just a matter of street violence or online harassment, it is orchestrated by the state. Governments that fear independent journalism resort to legal harassment, criminalization of reporting, illegal surveillance, and smear propaganda to turn female reporters into enemies of the regime.

A paradigmatic example is Iran, where two women journalists, Niloufar Hamedi and Elaheh Mohammadi, were arrested in 2022 after covering the case of Jina Mahsa Amini, the Kurdish woman who died in custody of the “morality police.” Both were accused of acting against national security and spent over a year in prison before receiving long sentences. The CPJ reported that their only “crime” was informing the public with a gender perspective about a story that sparked nationwide protests.

In Nicaragua, Ortega’s dictatorship has nearly dismantled independent media. Women journalists like Lucía Pineda Ubau and her colleagues at 100% Noticias have been imprisoned, exiled, and stripped of their nationality. Pineda was released in 2019 after six months in inhumane conditions and now continues her work in exile, as she recounts in interviews with DW and RSF.

In Russia, the case of journalist Elena Milashina, renowned for her reporting on Chechnya and human rights, shows that even well-established journalists face systematic violence. In July 2023, Milashina was brutally beaten by armed men while covering a trial in Grozny. Her laptop was destroyed, her head forcibly shaved, and she received death threats. Reporters Without Borders denounced the attack as part of a state strategy of terror against investigative journalism.

The use of defamation, espionage, or even terrorism laws as censorship tools has grown. These laws are often aimed not only at punishing the information shared but also at stigmatizing female journalists as foreign agents, traitors, or threats to moral order, reinforcing deeply rooted misogynistic stereotypes.

In these contexts, censorship is not always carried out through bullets or imprisonment. It often operates through fear, professional isolation, constant surveillance, and reputational damage, leaving scars that are invisible but just as effective in silencing.

-

Resistance: when reporting becomes self-defense

In the face of structural violence, imposed silence, and institutional censorship, many women journalists have chosen not to be silent. From digital trenches, community media, or newsrooms in exile, they practice a journalism that not only informs, it resists, protects, and transforms.

Globally, support networks have emerged to offer legal protection, psychological support, and digital security tools to at-risk female reporters. Initiatives like the Coalition For Women In Journalism (CFWIJ) and UNESCO’s program on the safety of women journalists provide technical support and visibility for those under threat.

These networks also serve as professional sisterhoods where sharing experiences of harassment, censorship, or exile is not seen as weakness, but as collective healing.

As journalist and human rights advocate Jineth Bedoya, kidnapped and raped in Colombia for reporting on paramilitary groups, says: “Journalism is what gets me up every morning. I am here and I breathe because of journalism; it is a way of life.” Her case was taken to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which held the Colombian state responsible for omission and negligence.

Similarly, Iranian journalists Hamedi and Mohammadi have been honored with the UNESCO Guillermo Cano Press Freedom Prize for their courage, showing that even in the harshest contexts, the international community can amplify their voices and demand justice.

Conclusion: no press freedom without free women

Violence against women journalists is not a “collateral consequence” of authoritarianism, organized crime, or war, it is a systematic strategy to exclude them from public life. It is, in many cases, a message to all women: “This is what happens when you speak.” And yet, they keep speaking.

In the face of fear, self-censorship, or exile, many choose to speak up. To condemn. To report.

Protecting women journalists is not just an act of sectoral solidarity, it is an essential condition for ensuring freedom of expression and the right to information for all of society. Because when a female reporter is silenced, what is lost is not only one voice, but also the possibility of understanding the world from another perspective.

And without that perspective, democracy is impossible.

The women mentioned in this article represent just a small fraction of the many female journalists who face danger and repression around the world. At Free Press Alliance, we honor their courage and call on everyone to let their bravery inspire us to take action, and to never remain silent, in the defense of press freedom worldwide.